Semidiscrete Optimal Transport: Difference between revisions

Andrewgracyk (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Andrewgracyk (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

Since <math> \nabla \mathcal{E}(\varphi)_j = 0 </math> when it attains a maximum, we have the relation between the weights and the measure density that we established in the previous section. Note that the maximum is taken and not the minimum because our function <math> \mathcal{E}(\varphi) </math> is a concave function. The discrete summation contained within this function is linear, but an infimum of a linear function is evaluated for the integration part, making the overall function concave. | Since <math> \nabla \mathcal{E}(\varphi)_j = 0 </math> when it attains a maximum, we have the relation between the weights and the measure density that we established in the previous section. Note that the maximum is taken and not the minimum because our function <math> \mathcal{E}(\varphi) </math> is a concave function. The discrete summation contained within this function is linear, but an infimum of a linear function is evaluated for the integration part, making the overall function concave. | ||

Once we have discovered our optimal <math> \varphi_j </math>, the optimal transport map is is one in which any <math> x \in V_{\varphi_j} </math> is mapped to <math> y_j </math>. We have the mapping to a constant over each particular region, making the optimal transport map piecewise constant.<ref name="Peyré and Cuturi"> | |||

Revision as of 22:57, 11 June 2020

Semidiscrete optimal transport refers to situations in optimal transport where two input measures are considered, and one measure is a discrete measure and the other one is absolutely continuous with respect to Lebesgue measure.[1] Hence, because only one of the two measures is discrete, we arrive at the appropriate name "semidiscrete."

Formulation of the semidiscrete dual problem

In particular, we will examine semidiscrete optimal transport in the case of the dual problem. The general dual problem for continuous measures can be stated as

where denote probability measures on domains respectively, and is a cost function defined over . denotes the set of possible dual potentials, and the condition is satisfied. It should also be noted that has a density such that . Now, we would like to extend this notion of the dual problem to the semidiscrete case. Such a case can be reformulated as

Aside from using a discrete measure in place of what was originally a continuous one, there are a few other notable distinctions within this reformulation. The first is that denotes the c-transform of . The c-transform can be defined as . is used to denote . Furthermore, we note that our original measure is a sum of Dirac masses evaluated at locations with weights , i.e., .

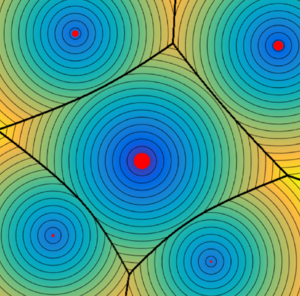

Voronoi cells to find weights

Now, we will establish the notion of Voronoi cells. The Voronoi cells refer to a special subset of , and the reason we are interested in such a subset is because we can use the Voronoi cells to find the regions that are sent to each . In particular, if we denote the set of Voronoi cells as , we can find our values of using the fact . Recall that refers to a density of the measure , i.e., . We define the Voronoi cells with

We use the specific cost function here. This is a special case and we may generalize to other cost functions if we desire. When we have this special case, the decomposition of our space is known as a "power diagram."[3] Using our power diagram as a domain of integration, we can successfully find the weights .

Finding the weights via the gradient

Finding the weights via the above method is equivalent to maximizing , and we may do this by taking the partial derivatives of this function with respect to . This is the same as taking the gradient of . In partial derivative form, we have

and in gradient form, we have

Since when it attains a maximum, we have the relation between the weights and the measure density that we established in the previous section. Note that the maximum is taken and not the minimum because our function is a concave function. The discrete summation contained within this function is linear, but an infimum of a linear function is evaluated for the integration part, making the overall function concave.

Once we have discovered our optimal , the optimal transport map is is one in which any is mapped to . We have the mapping to a constant over each particular region, making the optimal transport map piecewise constant.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

[2]

[1]

</references>

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 G. Peyré and M. Cuturi, Computational Optimal Transport, Chapter 5.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 F. Santambrogio, Optimal Transport in Applied Mathematics, Chapter 6.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMerigot